Sermons

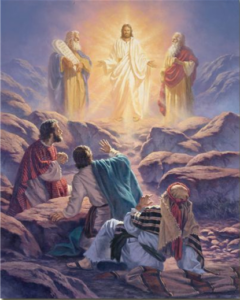

February 11, 2024 (Transfiguration)

“That’s Not Right!”

Mark 8:27—9:8

This is the last Sunday of the season of Epiphany. Epiphany is the word for when we suddenly and dramatically become aware of some new reality, aware that all is not as it seems. The season begins with the story of Magi traveling across the desert to see the new King of the Jews—a story that is found only in Matthew’s Gospel. It’s a high point in the story of Jesus, and it’s followed immediately by a terrible and tragic low point, when Jesus and his parents are forced to flee for their lives because King Herod (not the same Herod that was in our reading last week, but his father, or maybe grandfather) cannot abide the thought of a new king coming to take his place.

The season begins with Epiphany with a capital E, and ends with another epiphany, this time with a small e. But before we get to that we learn of a conversation between Jesus and his disciples.

It’s along the same lines as what we heard last week: people have been talking about Jesus, about who he is and what he’s about. Some say he’s Elijah come back to announce the arrival of the messianic age, others believe he’s John the Baptist raised from the dead, and others think he’s another one of the prophets the people know from their Scriptures. That’s what the disciples report to Jesus.

Jesus being Jesus, I doubt he’s unaware of this; it seems more likely that he’s setting the disciples up for his follow-up question: “But who do you say that I am?” Why are you with me? What do you hope to gain by being my disciple?

Peter, who seems to have emerged as the leader of the disciples, speaks for all of them and says, “You are the Messiah”—or in Greek, “the Christ.”

In Matthew’s Gospel,[1] there is more said after that, both by Peter and by Jesus. Peter doesn’t just say, “You’re the Messiah”; he adds that he believes Jesus is the Son of the living God—language that is part of the Good Confession we all make before we are baptized. It’s the occasion, in that Gospel, when Jesus gives Simon his nickname, Peter; and he tells him, “On this rock I will build my church,” which is the basis for the idea in Roman Catholic belief that Peter was the first Pope.

But here in Mark we don’t have any of that; Peter only says they have come to understand he is the Messiah.

The trouble is, the traditional understanding of who the Messiah would be and what he would do didn’t fit what Jesus told them next. The Messiah was meant to be a descendant of David—and all the Gospels make sure we know that Jesus is of David’s lineage—and he was supposed to raise a mighty army and destroy those who occupy the Jews’ ancestral land and oppress them with military might and crushing taxes, then take David’s throne in Jerusalem and reign from there forever.

Right after Peter says, “You are the Messiah,” Jesus says that he’s going to suffer, be rejected by the leaders of his people, and be killed, and then rise again after three days.

Wait…what?

Peter, again probably speaking for all the disciples, takes Jesus aside and tries to correct him. Actually, the language here is the same as what we find in the stories of Jesus casting out demons, and in the story from two weeks ago when Jesus calms a storm on the Sea of Galilee. It’s strong language: Peter isn’t just saying, “What in the text leads you to that conclusion?” as one of my seminary professors liked to ask us when we went off on some tangent that didn’t match up with what’s actually in the Book. He is chewing Jesus out!

Not surprisingly, that doesn’t go over well with Jesus, and he in turn chews Peter out. Calls him Satan!

I don’t think he means Peter is the devil, or possessed by the devil, or is somehow doing the devil’s work. He means that Peter is placing himself in opposition to what Jesus understands his ministry to be (this is what the name Satan means; most of the time in the Hebrew Bible it’s not a name but a title: ha-satan, “the adversary”).

He says, “Get behind me!”

The literal translation is something like, “Depart behind me”; or get away from me. But Jesus could simply be saying, Peter, get back in your lane; you’re trying to run in front of your leader; disciples are supposed to follow.

But I think it’s more than that, even. Because the disciples—probably all of those who are following Jesus, not just the Twelve—expect him to be a certain kind of Messiah, maybe Jesus wonders if they’re just following him because they think they might get the chance to be heroes, to gain some glory for themselves when he starts, as we say today, kicking Roman butt and taking names. So after rebuking Peter, Jesus turns to all of the disciples and explains that as they follow him on the way, they will have to set aside their desire for gain and glory, and instead, take up a cross.

We’ve sort of turned the notion of “bearing a cross” into simply putting up with irritation or discomfort, or having to deal with someone we find hard to get along with. The first disciples of Jesus—especially Mark’s first readers, who had just been through the “Great Revolt” that ended with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple—would have heard something different. For them a cross wasn’t a pretty thing to hang around their neck, nor was it simply a nuisance they had to put up with. They would have understood the cross as the instrument of a violent and horrible death, a symbol of oppression, injustice, and cruelty.

Our reading for today is a turning point in Mark’s Gospel. Everything from this passage on happens on the way to the cross. Stuff’s about to get real.

It’s not surprising the disciples don’t want to hear it, and not surprising that they refuse to understand. That could be why, a week later, the inner circle of disciples are shown another epiphany.

Scottish folk singer Dougie MacLean, during his concerts, sometimes recalls a conversation he once had with an elderly gentleman on the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides off the northwestern coast of Scotland. The conversation found its way into one of his songs:

The old man looks out to the island,

says this place is endless thin:

there’s no real distance here to mention;

we might all fall in…

No distance to the spirits of the living,

no distance to the spirits of the dead;

and as he turned his eyes were shining,

and he proudly said:

“I feel so near to the howling of the wind,

feel so near to the crashing of the waves,

feel so near to the flowers in the field;

Feel so near.

When Dougie introduces the song, he tells the story as though he doesn’t understand what the old fellow meant by “thin.” I find that hard to believe, but perhaps he tells it that way for the benefit of his audiences outside of the Celtic lands, since it is an unfamiliar term here.

Actually, it’s just the term that’s unfamiliar to us; I don’t really think the idea behind it is.

Even before they were Christian, the Celtic peoples had an understanding about “thin places,” and “thin times.” The term means times and places where the boundary between this world and the supernatural world—or, as we might express it, between earth and heaven—is thin, thin enough to be seen through or maybe even crossed.

Thin places include sites like Newgrange, north of Dublin in Ireland; or Stonehenge—although both those places were created well before the Celts came to the British Isles. Thin times include Imbolc, or St. Brigid’s Day, which happens right around what we call Groundhog Day; Beltaine, which over the years morphed into May Day; and Samhain, which became Hallowe’en.

Early Christians who were familiar with the stories in the Old Testament would have recognized immediately that, by taking Peter, James, and John up a mountain to pray, Jesus was taking them to a thin place. Because of the way people in the Ancient Near East imagined the world—a flat earth with a dome above it that separated earth from heaven—they understood mountaintops to be physically closer to where God is. They would have known of stories of people going to mountaintops for that purpose: Moses going to Sinai to receive the Law, and later to hear God proclaim God’s Name, for instance; and later Elijah going to the same place and encountering God not in earthquake, wind, or fire, but in sheer silence. They would recognize that the Temple in Jerusalem had been built on the top of Mount Zion for the same reason.

These early Christians would recognize the same thing about the light, and especially about the cloud—when Moses was up on Mount Sinai, remember, the people waiting down below saw the mountaintop enveloped by a cloud.

We have to be told what it means that it was Moses and Elijah, and not Joshua or Jeremiah or King David, who appeared and began to talk with Jesus. Mark doesn’t tell us what they talked about, but Luke does: his departure, his upcoming crucifixion; the Greek word for departure is exodus, and Luke uses that term on purpose. The early Christians would have recognized that Moses represents the Law, and Elijah was the greatest of the Prophets, and that by having them appear with Jesus, the Gospel writers mean for us to understand that the whole of the Hebrew Scriptures—our Old Testament—is fulfilled in Jesus.

But it seems like an experience like this in a thin place is never completely understood while it’s in progress. And it can be frightening; this is probably why Peter’s mouth kicks in gear before his brain engages and he starts babbling about building dwellings. This is partly another reference to the Old Testament story of the Israelites’ time in the wilderness, the one commemorated in the Jewish holiday of Succoth, remembering how when they were at Sinai and received the Law, they lived in temporary dwellings, booths, called succoth in Hebrew. But even more than this, Peter seems to want to memorialize the experience, build something tangible there that they can look at later and say, “That’s where it happened.”

His babbling is interrupted by the cloud—the symbol of God’s Presence—and a voice telling the disciples to listen to Jesus. And so they become silent…which is of course the first step if a person wants to listen to someone.

After our reading for today, Jesus and the Three go down the mountain, back to the everyday work of discipleship. And there is something strange going on: before the Transfiguration, before some of them saw Jesus transformed (the word in Greek is metamorphosis) and speaking with Moses and Elijah, before all that happened, the disciples had been able to heal people. But for some reason they couldn’t at this point.

It’s pretty clear from the description in the text that the boy they aren’t able to heal suffers from what we today might call a seizure disorder. The ancient people didn’t understand what seizures were or what caused them, and they didn’t have any means of treating them; without that understanding, seeing someone have a seizure was very frightening to witness. So they tended to interpret it as demon possession. The disciples have been able to heal that before, but now they can’t.

It really doesn’t say why; Jesus’ response is quite general, criticizing the entire generation for a lack of faith.

And we sure don’t want to go down the road of saying that this boy’s father and the onlookers are at fault for the disciples’ inability to heal the boy. We’ve heard that way too often, blaming a sick or disabled person, or their loved ones, for that person’s continued suffering, “If you just had more faith…” But those words are said only in passing; they’re said as a prelude to Jesus’ healing the boy who has what today we would call a seizure disorder.

And when that happens, I imagine the disciples, the boy and his father, and all the onlookers, realize they are in a thin place. It’s not through dazzling brightness and the appearance of long-dead ancestors that God’s glory is made known this time. It is through Jesus’ action in healing the boy, not isolated in some holy place but amidst the crowd, in the everydayness of his ministry.

We preachers often struggle to figure out how to apply a story like the Transfiguration to the everyday lives of us modern Christians. It’s not terribly likely that Jesus is personally going to take any of us up a mountain to pray with him, or that we will see God’s glory surround him, so we can’t apply the text by drawing lessons from it about how to behave or not behave when we find ourselves in this situation.

We sometimes visit thin places or experience thin times, what we might call “mountaintop experiences”—a lot of people who’ve been to church camp recognize that camp can be a thin place where we encounter God in ways we oftentimes don’t at home. Most of us who have staffed camps will remember kids asking why their churches can’t function like camp does, with intense, emotionally-charged worship in the outdoors, perhaps around a campfire.

It’s a hard question to answer; the reality is that a person can’t live full-time in a thin place. And if we keep both the reading for today and what comes after it in mind, we may recognize that just about any place—a mountaintop or a valley, a quiet time of prayer or a noisy public event, a campground or our own bedroom, a sanctuary or a city street, a temple or a cross—can be a thin place, if God chooses to make it so.

And if that’s the case, then one lesson we can draw is to be aware of that possibility, so that when God’s glory is revealed, however unlikely we find the setting, we don’t miss it.

[1] Matthew 16:13-20