Sermons

September 21, 2025 (Proper 20)

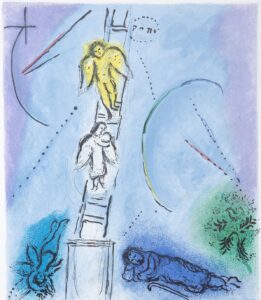

“Every round goes higher, higher…”

Genesis 28:10-19a

You probably know the old song by Creedence Clearwater Revival in which a musician finds himself stranded in a place he didn’t intend to stay: “Oh Lord, I’m stuck in Lodi again.”

Now I suppose if you’re from Lodi, you might not think it’s such a bad place; but it wasn’t where this fellow wanted to be. He wanted to be back home, and Lodi wasn’t home.

Ever been there? Maybe not stuck in Lodi, but in some place where you didn’t want to be, where you felt like even God didn’t know you anymore, and you couldn’t go back home?

If you have, then you know where Jacob was when our story opens.

He has to leave home in a hurry, with only what he can carry. His twin brother Esau is gunning for him because he had cheated Esau out of all the rights he should have had as the firstborn. He had cheated Esau out of his father’s blessing, a powerful thing in a patriarchy, a thing that can only be given once. Esau is, understandably, livid, and has promised to kill Jacob.

Luckily, Jacob has a place to go. His mother sends him back to her hometown, to the home of her brother Laban, where he can lay low until Esau cools off. But given the murderous rage Esau’s in, there’s not telling how long that will take. Jacob isn’t going to be able to come home for a visit, for a holiday, for dinner with the folks, nothing. He is a fugitive, on the lam, looking over his shoulder to make sure Esau isn’t following him…looking over his shoulder for a last view of home.

He knew about the God his grandfather Abraham had left home following, and he knew about the promise God had made to him at that time—a promise of land and innumerable descendants. He knew he was supposed to be the heir of that promise—however dishonestly he came by it—but maybe that promise wasn’t in effect when he wasn’t in the land God had given his family. All this had to have been going through Jacob’s mind as he was leaving home.

It was a lonely trip. He was really, truly alone, maybe for the first time in his life. At the end of the day he lay down to sleep in an unfamiliar place, a place we don’t hear the name of at first, and he has a dream.

Commentators have spent quite a bit of time trying to figure out what that ladder to heaven could have been. Was it an actual ladder, the kind we might stand on to clean out our gutters? Or was it a ramp, or a stairway, or maybe the side of one of those ancient pyramid-like buildings Mesopotamian people built as places where earth and heaven could meet?[1]

All this is very interesting, but it sort of misses the point of the story. When these kinds of visions show up in the Bible, they’re generally introductions, and what they’re introducing is the point.

So in this case, Jacob sees the ladder, or whatever it was, and the angels going up and down, and then God comes and stands beside him and starts talking. First God says, “I am the Lord, the God of your ancestors.” Then he restates the promise he made to Abraham, which transfers that promise to Jacob: “This land is yours, and your children’s, and you’ll have so many children you can’t begin to count them.”

But the rest of what God says is just for Jacob. “Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and I’ll bring you back here, and I won’t leave you until that happens.”

Jacob, a man on the run, away from the land God had given his grandfather, away from everything he’d ever known, away from everyone he’d ever known, gets the promise that he’s not alone. He’ll never be alone, no matter where he goes or what he does. He’ll never have to worry about whether his behavior changed God’s mind, whether maybe Jacob didn’t get to be the heir to the promise after all. God would always be with him and the promise was his. Period.

And so Jacob goes from that place, which he commemorates with a standing stone, a different man from who he was when he stopped there. He has met God, and he is changed.

It doesn’t necessarily make his path any easier, no. He ends up working for his uncle for fifteen years in exchange for two wives—one of which he didn’t want—as his uncle tricks him into marrying both his daughters, instead of just the younger one, Rachel, whom he loved from the second he laid eyes on her.

Nor does it make him any less prone to tricking others: As he’s preparing to go back home, he manages to swindle Uncle Laban out of the best of his flocks, meaning he has to leave Haran in a hurry, again on the lam—but this time wealthy, with flocks and wives and children and servants.

But that first night away from home, as he slept on the ground with a rock for a pillow, he is changed. He is now God’s man, and that informs all of his life from then on. Fifteen years after that first night, after his sojourn at his uncle’s home, his transformation is completed when he meets God again by a stream called Jabbok and gets a new name.[2]

It’s very rare in the Bible that a story like this is just about the events of the story. It’s worth mentioning, since the Narrative Lectionary doesn’t give us the story of Jacob’s second encounter with God, what that new name will be. He will be called Israel—which means “one who struggles with God”—the ancestor of a people who bear his name. The promise to Jacob is a promise to all his descendants, all those who bear the name God gave him at the ford of the Jabbok.

The book of Genesis ends with Jacob and all his family moving to Egypt, where there is food thanks to the wisdom of his son Joseph. But when the book of Exodus starts, centuries have passed and the fortunes of Jacob’s—Israel’s—family have changed. Now they’re slaves in Egypt, far from the land that had been promised to Abraham. The deliverer of the people, Moses, had not yet been born, and the people were suffering the cruelty of slavery and even genocide.

But in the midst of this, their storytellers would remind them how one day their ancestor Jacob slept with his head on a stone for a pillow, and God promised to bring him back to his land. If God promised that to our ancestor Israel, they said, the promise is good for us, too. We will go home. We will see the standing stone at Bethel, the House of God.

And they did. God was with them, and that made all the difference. God’s presence changed them from slaves into free people.

But centuries later, the people again found themselves in a foreign land, far from the Promised Land, exiled by a conquering empire. They had looked over their shoulders for one last glimpse of home, and seen their beloved Jerusalem in ruins, the Temple of the Lord in flames.

For awhile they forgot about the promise. They sat in Babylon, weeping under the willow trees, unable to sing their songs of praise, wondering where their God was.[3] And then someone, perhaps as a protest of the prevailing mood, perhaps protesting the Babylonians’ gloating at having conquered them, told the story of Jacob. Told how he’d been traveling, alone and scared, unwillingly leaving his home, and God had come to him.

God was with Jacob always, and promised to bring him home. We are Jacob’s descendants, that exiled storyteller said. That promise is for us, too. We will go home one day. We will rebuild the Temple. We are the people of God, wherever we are.

Not all of them went home. But they found that didn’t matter as much as they had thought it did. It didn’t matter, because God was with them wherever they found themselves. And that made all the difference. God’s presence changed them from people without a country into people who didn’t need a country to know who—and Whose—they were.

After 9/11, a couple of TV preachers said it was possible God has deserted the United States, no longer protecting our nation because of various public and private sins. They said God may have let the terror attacks happen. They listed the usual litany of sins, mostly having to do with what people do with the parts of their body that are covered by a bathing suit, and argued that God allowed the terrorists to attack us as punishment.

But I think they’re wrong. They are wrong because God has made a promise.

If you read the stories of the covenants, the promises, God made to Abraham and Jacob, to Moses and the people, in every one of them, God takes initiative. God acts first. God makes promises that are binding regardless of what we might do. That’s God’s grace.

Christians, Jews, and Muslims are all heirs to the promises God made to our ancestor Abraham. If God makes a promise, God will not withdraw that promise, as long as the universe exists. And the main promise to Jacob is that God will be with us, no matter what, no matter where, no matter when.

That doesn’t mean bad things will never happen. If you’ve lived on this earth more than about ten minutes, you know that bad things happen, sometimes they’re senseless, and frequently they’re not what we think we deserve. But God is with us. God is not making bad things happen to us.

At the end of today’s story, Jacob responds to his encounter with God. He recognizes God’s presence with him, immediate and ongoing. And he responds by setting up a memorial and making an offering. He saw things differently after that.

Intellectually, we know God is with us—that God will never break the promise always to be with us. But sometimes we need to be reminded. When times are hard, when prices are going up and world leaders are rattling sabers, when we or our loved ones are in danger, we need to be reminded. We need, like Jacob needed, to have God show God’s self to us, to recognize God’s presence with us. And we need to respond.

Every Sunday in worship, God is present with us—as we sing, as we read and proclaim the Scriptures, and as we pray. Every Sunday during worship, we have a chance to respond to God’s loving presence. We have an invitation to discipleship, to follow Jesus in baptism or to rededicate ourselves to him. We have the chance to encounter God at the Communion Table, and for that encounter with God to make a difference in what happens Sunday afternoon, Sunday night, Monday, and all week.

[1] Scholars think this kind of structure may have been behind the “Tower of Babel” story in Genesis 11.

[2] Genesis 32

[3] See Psalm 137.