Sermons

October 26, 2025 (Proper 25)

Second-Guessing History: The Sequel

1 Kings 5:1-5; 8:1-13

When David grew old, there was quite a controversy about who would succeed him on the throne in Jerusalem. His oldest living son, Adonijah, assumed he would be king, and he began to act accordingly. But it had already been decided, and endorsed by God, that Solomon, Bathsheba’s second son with David (remember that the first one died as an infant), would be the next king. So there was some wrangling behind the scenes by the prophet Nathan and the priest Zadok, and some symbolic action featuring Solomon riding his father’s mule, after which Adonijah stepped aside and asked for Solomon’s mercy.

Then when David died, Solomon took the throne; but Adonijah continued to scheme, and eventually he was put to death.

Once Solomon’s reign was secure, the Lord came to him and said, “I will give you whatever you ask of me.” And Solomon asked for wisdom, so that he might effectively govern God’s people.

After that we have a story meant to illustrate Solomon’s wisdom. The story involves two women fighting over one baby—they had each had a baby, but one had died, and they were both laying claim to the living child. In order to settle the dispute, Solomon ordered the child to be cut in half, with half given to each woman. One of the women was fine with this, but the other said, “No! Don’t cut the boy in half; give him to her.” And Solomon recognized that this one was the child’s true mother, because she was prepared to give the child up rather than see him killed.[1]

In Sunday school we all learned how very wise Solomon was, wiser than any king before or since. But we didn’t get the whole story.

Was Solomon really the wisest king ever to rule? Is the only bit of evidence of his wisdom the incident wherein he figured out who was the mother of a baby by threatening to kill the baby?

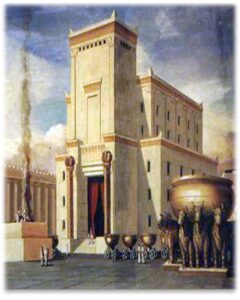

The historians in the Bible seem to be pretty ambivalent about Solomon and all that he did. That’s especially true when it comes to the building of the Jerusalem Temple.

There is great celebration when the Temple is dedicated—that’s the second part of our reading for today—but before that we discover that King Hiram of Tyre, an ally of Solomon as he had been of David, agreed to supply materials and labor for the Temple in return for Solomon providing food for Hiram’s household for years. We also discover that Solomon required forced labor from his people, and the burden of that labor seems to have fallen disproportionately on the northern portion of his kingdom. And that forced labor conscription doesn’t appear to have ended with the completion of the Temple and Solomon’s palace; in fact, it was still going on when Solomon’s son Rehoboam succeeded him.

Solomon had a ridiculous number of foreign wives, and they brought their own religious practices with them, and Solomon was tempted toward those practices and away from complete faithfulness to God.

Just as we learned with David’s misdeeds, such things don’t escape God’s notice. God declares that the kingdom will be torn from Solomon’s successor and given to another as a result—to one Jeroboam son of Nebat, whom Solomon had put in charge of all the forced labor from the tribe of Joseph.

Was Solomon truly so wise?

He might have started out that way, but over the years of his reign, something changed. Maybe he started believing his own press clippings, as the saying goes. Everybody said, “Oh, you’re so wise!” And Solomon got to thinking, well, God gave me wisdom, so the decisions I make must be good and wise ones. And maybe he got complacent and just assumed nobody would ever tell him no.

I actually think Solomon’s lack of wisdom first showed its face in the first part of today’s reading.

When his father David got the notion to build God a Temple, the first thing he did was ask God, through the prophet Nathan, if it was the right thing to do. And God said no. But God also said that David’s son would eventually be allowed to build the Temple.

When Solomon was secure on his throne and his mind turned toward the building of the Temple, did he go to God first? Did he ask if God still wanted him to build a Temple?

Nope.

Maybe Solomon didn’t go to God first because he didn’t want to put himself in a position where he might be told “no.” A lot of powerful people don’t like to be told “no,” and so, like Solomon, some of them just barrel ahead with their plans because if they stopped to ask, they just might hear that little two-letter word that would bring it all to a screeching halt.

What if Solomon had asked God first? What if God’s mind had changed, but Solomon couldn’t know that because he never bothered to ask? What might have been different?

Would he have treated his people more fairly, and not given away so much of his country’s resources to a foreign ruler? Would his kingdom have held together after his death? Because that “never tell me no” mentality was magnified with his son Rehoboam, and he promised to increase the burden of forced labor that his father had placed on the shoulders of his people.

And at that, the northern tribes, who felt they had been unfairly targeted, rebelled and formed their own nation under the aforementioned Jeroboam son of Nebat. Only two of the original twelve, Judah and Benjamin, remained loyal to David’s house.

What if Solomon had asked God before starting? What if Solomon had sought God’s wisdom, which was greater than even his own?

Second-guessing history is awfully tempting when we look back and see the mistakes that were made and the consequences of those mistakes. But it really can be nothing more than a thought experiment to keep us occupied for awhile. We can’t change what David or Solomon did.

But we can see what the temptations they gave in to were and their consequences. And we can recognize that people—we—still face the same temptations, and maybe we can learn from their mistakes so we don’t make the same ones.

If we’re in positions of authority, we need to make sure we have people advising us who are able to tell us “no”—and then we need to listen to them. Trust me when I say this is something even pastors need. Some of the worst church scandals I’ve been aware of have happened when pastors decide they alone get to make all the decisions, and eliminate the governing boards and other structures that keep them accountable.

And whatever our position, whether we have authority or not, we have decisions to make from time to time, and those decisions can affect not just the present but also the future. So another major lesson we can learn from Solomon is that everything we do should be bathed in prayer. Even the greatest earthly wisdom pales in comparison to God’s wisdom, and thus if we ask God for guidance, we’re going to make better decisions that have better outcomes.

[1] The accounts of Solomon’s ascent to the throne of David and his wisdom can be found in the first three chapters of 1 Kings.