Sermons

May 18, 2025 (5th Sunday of Easter)

One Long Sunday

Revelation 4

Some years ago, The Christian Century reported on a study some anthropologists or someone had done. What they discovered was that nearly all human beings are musical. Something like 95 percent of people are capable of making music of some kind. That means that out of every 100 people, only five are completely hopeless when it comes to music.

(George Clooney is apparently one of the five, incidentally. When he was getting ready to star in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, he wanted to do his own singing. He took lessons and worked really hard…but he just plain couldn’t get it. They had to have him lip-sync someone else’s singing.)

I expect it comes as something of a shock to some of us here that nearly everyone can make music in some way. We’ve been taught that music is something that takes great skill and extensive training, and only those who are born with particular talent should put in the time and effort it takes to learn how to make music well, maybe even well enough to be professional musicians, who make music while the rest of us watch and listen. But it’s just not true! That way of thinking about music is something new, only since we’ve been able to record music and play it back, really.

Now I don’t mean to say that there haven’t always been people with exceptional musical talent, nor that there haven’t pretty much always been professional musicians. But what I do mean is that it’s only been fairly recently that we’ve decided music is something better left to the professionals.

For some people, having been taught that we’re not really musical and have no business trying to be, church is the only place where we’ll do any singing at all. And what we sing in church, what kind of music we include in worship, is one of the greatest sources of contention we have.

We can tolerate a preacher who puts us to sleep. We can live with bad coffee after the service—although if you are on the board and decide to have a cup during our meeting this morning, what you’ll be drinking isn’t bad. But mess with the music, and you’ve got a fight on your hands.

I have mentioned before letters that pastors and music leaders have received criticizing “modern” music that has been introduced in worship. These letters indicated disapproval of rhythms that were too fast, styles too much like popular music heard outside of church, words and images that are too emotional, theology that is too shallow.

But here’s the interesting thing: not all those letters were written recently. They weren’t necessarily written in the last 40 years or so, as contemporary worship services and praise bands became part of many churches all over the world. At least one I know of was written around 1880, and the new songs the writer was complaining about were songs like these:

“Sing them over again to me, wonderful words of life…”

or “Shall we gather at the river, where bright angel feet have trod…”

or “Blessed assurance, Jesus is mine; O what a foretaste of glory divine…”

or “Softly and tenderly, Jesus is calling, calling for you and for me…”

The issue of what music could be part of worship is one that has been inciting strong feelings for a very long time!

Once upon a time, a young man got to complaining about the horrible state of music in his church. In those days and that place—England, around 1700—the church insisted that the only songs that could be sung in church were strict metrical translations of the Psalms. Some of them, because the poetry had to be constrained into such a narrow framework of appropriateness, were really awful. So that young man, Isaac Watts, began to write his own paraphrases of the psalms, preserving the meaning while making them much more poetic than the strictest translations were.

He got into trouble for it, but because of Dr. Watts we have favorites like “O God, Our Help in Ages Past” (based on Psalm 90), “Joy to the World” from Psalm 98, and his beautiful setting of Psalm 23, “My Shepherd, You Supply My Need.” And before long Dr. Watts expanded his hymn writing focus a bit, and began to write hymns that weren’t Psalm settings, including “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross.”

Why is church music such an issue? Why, if most of us believe we aren’t musical, do we care so much about what we sing and hear in church?

Well, first it’s because most of us are musical, even if we aren’t professional or even trained musicians. Second, it’s because when a group sings together, they are breathing together—a powerful way to nurture community. And it’s because we know that we’re doing something even more important than that.

In the fourth chapter of Revelation, John is shown a vision of heaven. This vision comes right before all the awful stuff in the book—the plagues, the beast, the horrors and woes. John sees the throne and the one seated on it because he needs to know there is still Someone in charge who has far greater power than the Roman Emperor and the other powers of this world and of evil could ever imagine having.

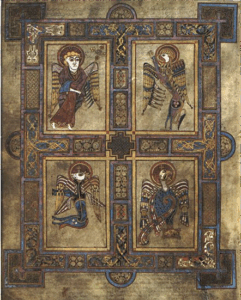

He sees a throne, and someone seated on the throne—“the One seated on the throne” is John’s most commonly used reference to God—and all sorts of people and creatures gathered around the throne. The twenty-four elders represent the ancestors of the twelve tribes of Israel and the twelve apostles. The four living creatures represent all the animal life on earth—humans, domestic animals, wild animals, and birds. They have six wings each—as the seraphim do in Isaiah’s vision described in the sixth chapter of his book—and they’re described as “full of eyes,” which is a way of saying they are eternally watchful.

What are these people and creatures gathered around God’s throne doing? They are worshiping. They worship God endlessly—and part of their worship is singing. Carol Ann included in our service today two hymns that were adapted from the hymns John heard in his vision: “Holy, Holy, Holy” and “Thou Art Worthy.” There are lots and lots of songs in Revelation. The “Hallelujah Chorus” from Handel’s Messiah is based on Revelation 19:6 and 11:15.

A long time ago some devout people liked to describe heaven as “one long Sunday.” That didn’t really appeal to a lot of children, who were prevented, after a long week of sitting quietly at desks and doing chores before and after school, from playing or having fun of any kind because of rules about what was allowed on Sundays. Adults would have seen it differently; after working hard all week, they came to a day where nothing was required of them, where they could rest. Kids didn’t want to rest, though; they wanted to play, and the rules said they couldn’t.

The people who described heaven as one long Sunday, however, weren’t thinking about it being a day of rest, nor yet a long, boring day where you couldn’t do anything fun. They were talking about what John describes in Revelation 4.

Heaven, so John tells us, is a place where all the inhabitants, people and all other creatures, engage in endless worship of God. And then, later in Revelation—as we’ll see in a few weeks—when all the terrible things are over and the world is remade, this endless worship becomes the order of the day for all of creation.

Our worship here on earth is thus a rehearsal for the time when we are all in God’s presence forever and ever.

And so we’re doing something very, very important when we gather on Sunday mornings. Somewhere deep inside we know this, even if we come to church dressed casually, even if we come to church because we have to, not because we want to.

We are all musicians, in one way or another, and when we gather to worship our music follows the example of the heavenly court that sings as part of their endless worship of God. So yes, we care very deeply about the style and quality of music that is part of our Sunday worship.

I also believe that, because we are rehearsing for the day when we join that endless worship service in heaven, it doesn’t do for us not to sing and make music—to stand, or sit, and listen while others make music for us. When we come to church on Sunday morning, we’re not coming to attend a performance, to watch and hear someone else read and speak and make music. We—all of us—are the performers. It’s no more appropriate for us to skip worship, or come but decline to participate because we “don’t like that music” or think we can’t sing, than it would be for some of the members of an orchestra to sit with their instruments in their laps while everyone else performs.

We’re not the audience when we come here on Sunday morning. God is the audience.

God is the audience of the performance we call worship—and one day that worship will be more than performance; in the new and restored world God will bring about at the end of all the troubles of this world, worship will be a way of life.