Sermons

October 20, 2024 (Proper 24)

A Mixed Blessing

1 Kings 5

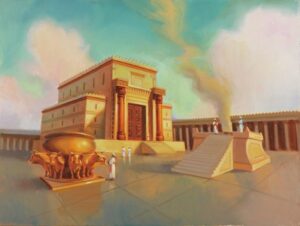

Looking back at it from here, I’m not sure that Solomon’s temple was an unqualified good for his people.

It was a great and magnificent building project, one in which many of Solomon’s people participated. Such building projects often bring a people together with a common purpose, sort of like fighting, supporting, and ultimately winning the Second World War brought the people of many nations together. That isn’t a bad thing, of course. But in the case of the temple, not everybody who worked on it did so voluntarily.

The system of forced labor Solomon instituted to get the temple built is called corvée; it’s how public works like roads and temples and such got built in the ancient world. Every able-bodied man—women didn’t typically work on this kind of project—was required to put in a set amount of time on these projects. (These days, of course, we pay our taxes and then the local, state, and federal governments hire people to do the work; we’re still asked to do our part, but it’s a little more indirect.) What that would have meant for Solomon’s people was that for one month out of every three, men would be out of the country, away from their families, from their crops and livestock, from whatever trades they might have worked at. This was done on a rotating basis, so a third of the men drafted into the project would have been away each month.

Maybe the ones who were off in a given month would have picked up the slack for the ones who were gone. I don’t know. In any case, I rather prefer the way we do it now, even if I do sometimes chafe when I see the bottom lines on my tax returns and bills.

Imagine being a farmer and being called away from your land at planting or harvest time, or a builder having to leave your shop or job site during the peak season. Imagine being a teacher and having to take a month off in the middle of the school year. Imagine being a doctor or nurse and… well, I think you get the picture.

Yes, everybody did their part to get the temple built, but at what cost? By the time the temple was finished, everybody could look at it and say they had a hand in its building…but they might also look at it and say it was a bit of an inconvenience, or even that their family’s livelihood took a hit.

It would have been a mixed blessing.

It was a mixed blessing because the system of forced labor Solomon put into place to get the temple built continued after it was finished, and it became even more burdensome under his son, Rehoboam.

It got so bad that the people who lived in the northern part of the kingdom seceded, led by a rebel named Jeroboam son of Nebat, who became their king. That northern kingdom followed a path that led them far away from what was right in the sight of God, and eventually their country was destroyed by the Assyrian Empire. This is the origin of the legend of the “Ten Lost Tribes of Israel”; stories abound of where these lost tribes went and who they became. Chances are that some of them went south to Judah, others scattered but kept their identity, and some were absorbed and mingled with the people Assyria settled in their land from other places.

Without that system of forced labor—or because it didn’t end when the temple was completed—maybe the kingdom wouldn’t have split. Maybe there never would have been a King Ahab and Queen Jezebel. Who knows?

Over the years between Solomon’s time and the siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 587 bce we discover that the historians, at least, were pretty ambivalent about the temple. We actually see that for the first time in chapter 8 of 1 Kings, which describes the dedication service held after the temple was finished.

In our reading from 2 Samuel 7 last week, we discover that God, in the time of King David, saw the building of a temple—a house for God to live in—as an attempt to restrict God’s freedom of movement. Solomon actually acknowledges this in his speech at the dedication; but then he turns around and says, “I have built you an exalted house, a place for you to dwell in forever.”

In other words, “God, you said not to fence you in; I am now fencing you in.”

We think of our churches as “God’s house,” but in a much less literal sense than what David and Solomon thought about the temple as God’s dwelling place. We know that God’s presence is with us everywhere—David and Solomon should have realized this as well, even as they were determined to put God in one place. We can encounter God as surely in a field or a golf course or the kitchen of our own house as we can in this place. But this place is set apart specifically for the purpose of coming into God’s presence.

The temple was, too…but over time it sort of morphed into the one place where people could meet God. God wasn’t in the field or the kitchen or on the golf course (if ancient Israel had actually been in Scotland, where golf was first played); God was at the temple and if you wanted to be with God you had to go there.

The problem with that was that when the temple was destroyed by the Babylonian Empire, not just the people but also their God were made homeless. The people of Judah sitting in the ghetto of Tel Abib in Babylon wondered if God had abandoned them, if Babylon’s god Marduk had actually killed the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

And the Babylonians, fully aware of this, taunted them: “Where’s your God now?” Oh, that’s right: he’s gone. Nobody is going to save you. Why don’t you sing us some of those cute little songs you used to sing as you walked up Mount Zion to meet your dearly departed God…maybe the one that starts with “Out of the depths I cry to you…Lord, hear my voice!”[1] The words don’t mean anything, but we kind of like the music.

Those exiles—and the poor people the Babylonians didn’t bother rounding up and hauling off, but left in Judah to try and eke out a desperate existence—would have been in a major crisis, because if God’s house had been burned down, maybe God had died in the fire. The temple was a mixed blessing, because when it was no longer there, the people didn’t know what to do or whether God would ever be heard from again.

But as you do, when you find that your whole world has been demolished, when the ground on which you stood has been snatched out from under your feet, the exiles kept putting one foot in front of the other. They cried out, as they had cried out when they were enslaved in Egypt, on the off chance that God was still out there somewhere and might hear them. They cried out things like, “O daughter Babylon, you devastator! … Happy shall they be who take your little ones and dash them against the rock!”[2]

And somehow, having poured out their misery, they found in the space it left behind a glimmer of hope. Maybe, even here, God hears us. Maybe one day God will save us. Maybe we can figure out a way to be God’s people even in a foreign land.

And that is what they did. They gathered their stories, their recollections of God’s commandments, the early edition of Deuteronomy that they either carried with them to exile or re-created from memory there, and eventually began to put together the Bible, beginning with the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures, our Old Testament. They began to gather to pray, and to tell those stories and discuss the covenant and the commandments, in places that eventually came to be known as synagogues.

After the exile, when the Torah was completed in Babylon, it was brought back to Jerusalem and read to the people in front of the rebuilt temple.

The temple was a mixed blessing, and so was its destruction. Would the Torah, Genesis through Deuteronomy, have come into existence as it did if the temple had never been destroyed? Would there have been an institution—the synagogue—in place when that rebuilt temple was also destroyed, by the Roman Empire, in 70 ce, that made it possible for the Jewish faith to continue even without the temple?

My college degree was in secondary education—I was certified to teach grades 7-12—with specialty in social studies. That meant I had roughly the equivalent of a major in history and a minor in political science, with some other coursework and the foundations of the art of teaching, under my belt when I graduated.

Studying history as I did in college leaves a person with a long view of the world and what has happened in it. Historians see patterns, cycles, unintended consequences, mixed blessings, and the way humanity seems to forget the mistakes of their past so that we repeat them over and over.

When I look at the story of Solomon’s temple, I see it in the context of the life of the people who built it, who lost it, who rebuilt it, who lost it again, and who kept having to figure out how to be God’s people in new circumstances. I see the good news and the bad news.

The good news is that the people now had a place where they knew without a doubt that God could be found. The bad news is that they came to believe it was the only place where God could be found. The worse news is that when it was destroyed, they weren’t sure they could find God anywhere.

The good news is that they learned God was with them even in exile. The better news is that as they figured out life in exile, they began to assemble the Book that has guided millennia of their people—the Jews and, by adoption, us Christians—as we try to figure out how to live faithfully no matter what’s going on around us. And the best news of all is that that Book tells us that one day we will all live eternally in God’s presence in a place where all the bad news has been deleted.

[1] Psalm 130:1-2

[2] Psalm 137:8-9