Sermons

April 7, 2024 (2nd Sunday of Easter)

“…to the ends of the earth”

Acts 1:1-14

The first human being walked on the moon three days after my first birthday. My dad says I watched it on TV, but I don’t remember it.

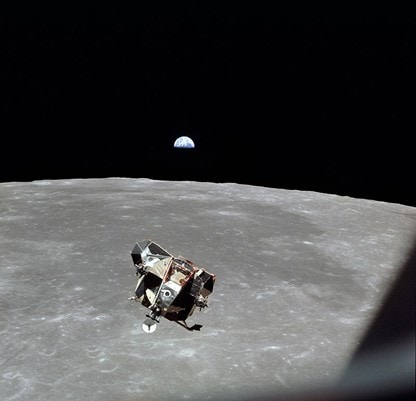

The three astronauts on the Apollo 11 mission carried cameras with them, and they took a number of photos that have become iconic. One of the most haunting was taken by Michael Collins, as he orbited the moon in the command module Columbia while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin[1] went to the moon’s surface in the lunar module, the Eagle. The picture has been called “Every human being except Michael Collins.” It shows the lunar lander on its way to the moon, with Earth rising in the distant background.[2]

The photos the three astronauts took, especially that one by Collins, are truly spectacular, and the idea of human beings walking on the heavenly body that gives us light at night, having a picture of the planet we live on taken from that heavenly body is mind-boggling. It has implications for our theology, most particularly for our understanding of the cosmology described in the Bible relates to the understanding science has shown us.

We’ve all heard the stories of how science began to understand that the earth is not the center of the universe, and that the sun, moon, and stars do not revolve around the earth on a dome that holds back the waters above and separates us from heaven. When Copernicus first discovered that, many centuries ago, and began to tell others about his discovery, the powers-that-be of the church threw a fit and fell in it.

Copernicus was followed by Galileo, who was excommunicated for his beliefs, and was only pardoned by the church in the last century.

When people finally went into space, and saw the earth from the lunar surface, we knew for certain that Copernicus and Galileo were right. There’s no firmament, no dome that separates the waters below and the waters above. The mountains don’t hold up the sky. The moon, sun, and stars don’t move across that dome; and there are no little windows in the dome that God can open to let the rain out.

And the people who have traveled into outer space didn’t find heaven out there somewhere.

We still don’t know exactly where heaven might be, where God lives. But what we’re pretty sure about, based on modern scientific knowledge, is that you can’t start on the earth’s surface, defy gravity and rise up into the air, and be in heaven right after you disappear into the clouds.

The trouble with this, of course, is that there are several places in the Bible where different people are depicted as doing just that—Elijah ascended to heaven on a fiery chariot as Elisha watched, for instance[3]—and there are also legends that say the same thing happened to Moses, even though that’s not in the Bible. And after Easter every year, Christians celebrate the Ascension, and read this text from Acts that says Jesus also ascended from earth into heaven.

So what do we do with this story?

Having lived all but the first year of my life in the days after people first walked on the moon, I am not sure I’ve heard many preachers deal with this story. What can we do with a story of an event science tells us can’t possibly have happened as the Bible presents it?

If we deal with it as factual, a literal description of something that actually took place at a specific point in history, we open up a great can of worms: Where is this heaven we’re saying Jesus ascended to? How did it happen—given that gravity, as a bumper sticker I saw once said, is not just a good idea; it’s the law, a law even Jesus would have been bound by as long as he lived on earth as a human being?

And what do we do with all the things science tells us about the universe, about where the moon is, where the stars are, what it’s like out there? Do we have to throw out all knowledge science has given us—to believe as some odd folks here and there still do that the moon landing was faked, a giant and well-preserved hoax?

But on the other hand, if we deal with it as “just a story,” something that could not possibly have happened, because of course we know better now that we have science and the technology to study outer space, we have other questions: If we don’t believe a story in the Bible really happened as it’s written down, then is there anything in the Bible that we can believe, or is it all a pack of lies? And if a story like this one didn’t really happen, then it can’t possibly have anything to say to us today about our own live of faith, can it? Where can we find truth in a story that modern science says is impossible? If I actually choose to preach a text like this as the Word of God, wouldn’t I be asking the folks who hear it to check their brains at the church-house door?

I have a feeling this may be the reason why we don’t hear a whole lot of sermons about the Ascension. And I have no idea how it happened that the risen Jesus, who was seen by many, many eyewitnesses in the days following the first Easter, went away and was seen no more.

My suspicion is that the story of the Ascension is a metaphor—like the fantastic descriptions of the New Jerusalem in the book of Revelation, this story is an attempt to put something into words that is far too big, far too incredible, for mere words. They said, “I can’t describe it,” but then if they wanted to get their point across to anyone else, they had to try to describe it. So they said, “We were there with him, and we asked him a question, and he answered it, and almost before he quit talking it was like he just rose up and disappeared.”

I can’t pretend to have any idea what really happened—except that Jesus, who had been raised from the dead and whom they had seen after that, wasn’t with them anymore, and they understood him to have gone back to the Father, to God. But I don’t personally think we have to believe this story happened exactly as it’s written down in order to find truth in it. I don’t think a story that is in the Bible has to have happened exactly as it’s written down in order for it to be the Word of God. So there has to be truth here; there has to be something God is trying to say to us this morning.

Let’s look at the story, and see if we can find it.

The first few verses of the book of Acts are introduction; Luke mentions Theophilus, as he did at the beginning of his Gospel. This leads us to understand Acts as a sequel to Luke, written by the same author.

After that introduction we learn that Jesus spent forty days meeting with the eleven disciples, and he told them to stay in Jerusalem and wait for the coming of the Holy Spirit, which had been promised by the Father. Then they asked him a question: “Now are you going to restore the kingdom to Israel?”

They still don’t seem to get it—even then, after he was crucified and raised, Jesus was not going to raise an army and overthrow the Romans and re-establish the throne of David in Jerusalem forever. So he very quickly dismisses the question: “You don’t get to know when that’s going to happen.” But, he says, “When the Holy Spirit comes to you, you will have the power to be part of the restoration of the kingdom: you will be my witnesses, starting here in Jerusalem, and expanding out into all the world.”

And that’s when he left them. No goodbyes, just gone.[4]

The disciples stood there slack-jawed, staring in the direction they thought Jesus had gone, until a couple people in white robes showed up. These two could be the same two that appeared to the women at the empty tomb in Luke’s account and asked, “Why do you look for the living among the dead?”[5]

This time, they ask, “Why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” Literally translated, the Greek verb in this sentence means something like, “Why do you stand there with your eyes in the sky?” They tell the disciples, “Look, he’ll be back—someday he’ll come back exactly like he just left.”

Luke doesn’t report any response given by the disciples to the two people, whom we’re probably supposed to understand as angels, and the angels don’t tell them to do anything; but in the next sentence the disciples go back to Jerusalem, back to the upper room. They go back and they do what Jesus had told them to do: wait for the Holy Spirit to come.

They stop doing what they’re not supposed to do: speculating about when the end-times will come, and standing there staring at the sky, mouths hanging open, completely stuck in the moment and unable to move forward.

As they stood there catching flies, they forgot that there was something important they were supposed to be doing. When the two angels asked their question, “Why are you standing there like a bunch of idiots staring at the sky?” they remembered. And once their minds kicked back into gear, they went back to Jerusalem to wait, just like Jesus had told them to do.

It was, at least according to tradition, about ten days later that the Holy Spirit finally did come to them—on the day of Pentecost, which we won’t get to until a few weeks down the road. In the meantime, the eleven disciples waited, along with a number of women (including Jesus’ mother), and his brothers.

And here, I think, is where we might find some truth for us today.

We live in a time when things are changing so fast that we can’t always keep up. Frankly, a lot of the time we don’t know that we really want to keep up. Some of those changes are quite uncomfortable.

Technology outpaces just about all of us—and in a lot of cases it outpaces our morals and ethics, just like what happened in the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution.

The ethnic makeup of our country is changing; some people find that exciting and positive, while others are afraid something critically important may be lost in the process.

The number of people in the United States who call themselves Christian is decreasing—actually, the number of people who claim any religious faith at all is going down, the people who study such things tell us.

In churches, we find things that used to work very well just don’t work anymore. We aren’t the center of community life anymore; people don’t look to the mainline church for guidance on public policy or much of anything else. People won’t come to church just because it’s what you’re supposed to do; folks don’t necessarily flock to us any time we open the doors.

Very few things we have tried to do to get ourselves back on track have had much effect. And we don’t have a good picture of what the future might hold for us—for our churches, for our own lives, for our city or our country. We find ourselves a lot of the time stuck in a moment, just like the disciples were at the ascension: we just look, and look, at what used to be.

But God wants to do something new with us—just like he had promised these disciples that he would do something new with them: send the Holy Spirit and make this clueless bunch of people into witnesses to Christ’s life, death, and resurrection, not just among their own ones in Jerusalem and Judea but all over the world.

And so perhaps we would be best served if we would follow the example of these eleven, plus the women and others who were with them in the upper room, after the two people[6] in white robes snapped them out of that moment they were stuck in: gather ourselves together as disciples of Christ, and devote ourselves to prayer as we wait for God to act. For it was into that gathering of disciples, as they were praying, that the Holy Spirit’s life-giving power came—and it will be the same for us.

[1] While Armstrong and Aldrin waited on the lunar module for their scheduled walk on the lunar surface, Aldrin, an elder in the Presbyterian Church, took Communion. See https://www.history.com/news/buzz-aldrin-communion-apollo-11-nasa.

[2] See https://twistedsifter.com/2021/04/michael-collins-1969-apollo-11-photo-of-every-human/ for the story of the photo and Collins’ experience.

[3] 2 Kings 2:1-12

[4] We have a slightly different version of the Ascension story at the end of Luke: “Then he led them out as far as Bethany, and lifting up his hands, he blessed them. While he was blessing them, he withdrew from them and was carried up into heaven” (Luke 24:50-51).

[5] Luke 24:5

[6] I know the text says “two men,” but I’m given to understand that angels don’t have gender, so I’ve opted for a non-gender-specific term.