Sermons

February 1, 2026

“This isn’t the time or the place.”

John 2:13-22

The weather outside sure doesn’t look like it, but spring is coming.

For a lot of us, with spring comes spring cleaning. All winter long we do everything we can to keep the house as fresh and clean as possible when it’s closed up and everybody’s cooped up inside, and if we go outside when the weather’s bad we track in mud, snow, road salt, and you name it when we come back inside. We try to keep clutter under control, the clutter that accumulates when nobody really feels like doing much other than wrap up in a blanket and watch TV.

If we’re lucky, we can hide the clutter behind cabinet doors, or as neatly stacked as possible until it begins to defy gravity. We run the sweeper, spray air fresheners, light candles, whatever it takes. But eventually all the cabinets and air fresheners in the world won’t hide the fact that the house needs to be opened up and really cleaned. And eventually gravity exerts itself on those stacks and piles of papers and other assorted stuff we’ve put off dealing with until some unspecified “later.”

Then the weather warms up, and the birds start singing, and before long it’s time to start the spring cleaning. But if you’re like me, you look at the mess, and you don’t have a clue where to start, so you don’t.

My mom discovered a trick when I was a kid with a messy room. She figured out that the best way to get me to clean my room—really clean it, not just sit among the junk and read the books I was supposed to be putting away on the shelves—was to make me really mad. Worked every time!

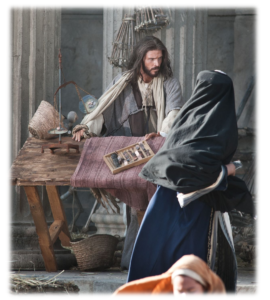

Tradition has it that the story we read today from John’s Gospel—and it’s actually one of the few stories that’s in all four Gospels—is an account of a time when Jesus got really mad, and that anger resulted in him doing some cleaning. It doesn’t really say so explicitly in any of the texts, but I don’t think it’s entirely out of line.

The difference between John’s Gospel and the other three is that the others have this story happening at the end of Jesus’ ministry. In fact, in the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) it seems that this incident is the tipping point that finally led to his arrest and crucifixion.

That’s not the case in John. John puts the story right up front. It’s still Passover, but John has Jesus go to Jerusalem for Passover at least three times, instead of just once like the others. (This is, incidentally, why we tend to think of Jesus’ ministry as having lasted three years.)

It’s worth thinking about why this story is at the beginning of the Fourth Gospel instead of at the end. Could be that John wanted this event, along with the story of the wedding at Cana, where Jesus changes water into wine, to set the tone for the rest of the story. On the one hand, we have a sign that demonstrates Jesus as the bringer-about of the extravagant goodness of God—and on the other, we have a scene in which Jesus completely disrupts the normal workings of the Temple.

In the church where I grew up, we were taught that the moral of this story is that nothing is to be bought or sold in a church building. No Girl Scout cookies, no kids with school fund-raisers, no youth group bake sales to raise money for a mission trip, no soup suppers to help fund the women’s group’s work, no nothing. That’s not what we’re here for, they would say; look what Jesus did to the people who were selling animals in the Temple. Jesus doesn’t want us buying and selling things in the church. End of discussion.

But you know what? I think the issue is a whole lot bigger than whether or not we have bake sales after church. I don’t really think Jesus gets his nose out of joint if there’s a table full of cookies set up in the foyer so we can buy them on our way out if we want.

Here’s the deal. This was Passover, which was one of the pilgrimage festivals, when anyone who was able was supposed to go to Jerusalem and worship at the Temple. Temple worship at these festivals included animal sacrifices, and everybody was expected to bring an animal.

But if you had to travel a long way, it might have been a major problem to bring an animal with you, along with its feed and anything else required to take care of it, so it could be sacrificed. So you might come expecting to be able to buy an animal nearer the Temple.

And thus there were people at the Temple who were offering animals for sale, unblemished animals like they had to be for the sacrifice. But I suspect the temptation to charge exorbitant rates for those animals would have been difficult to resist, when people have to have what you are selling and you’re the only one who has it for sale.

Then there was the matter of the tax everyone was required to pay in support of the Temple. Because of the commandment against graven images, no coin with anyone’s face on it—meaning any Roman coin that was in circulation—could be used to pay the tax. The Temple officials had determined that there was one specific coin allowed, and it wasn’t one everybody typically had in their pocket. So there was a man at a table in the Temple courtyard, and he’d be glad to exchange whatever money you had for the required coins—for a fee, of course. I don’t know what the exchange rate would have been, but it’s fair to suspect that if you gave the money changer $5 in Roman coins, you wouldn’t get back $5 in the approved coins.

Nothing wrong, of course, with a business person wanting to cover their costs, but I imagine that, just like with the people selling animals, an unscrupulous business person could take quite a bit more than they actually needed to cover those costs.[1]

Here’s what I think Jesus had a problem with. For a variety of reasons, the powers-that-be at the Temple—and in John’s Gospel they, but not necessarily the general Jewish population, were generally portrayed as greedy, power-grabbing collaborators with Rome—had turned the place where people were supposed to be able to encounter God’s Presence into a business. They set up barrier after barrier that people had to get through, hoop after hoop after hoop they had to jump through, before they had any chance to worship God.

And there were no doubt people who thought that was just fine—not just the ones who stood to benefit from the sale of animals and exchange of coins, not just the leadership, but even some of the worshipers themselves. As a colleague of mine put it, for some “faith had degenerated into something of an economic transaction: ‘I’ll buy a bird, sacrifice it, fulfill my religions obligation and move along.’ God would be appeased and the ‘worshiper’ wouldn’t have had a snowball’s chance in Hell of having an actual, transformative encounter with God the Creator.”

But it wasn’t just fine with Jesus.

God’s not short of cash—as Bono of U2 reminded us 35 years ago—and he’s not hungry, either. God wants a relationship with us, not a little of our money or a sacrifice to buy him off, so he’ll leave us alone for another week, or month, or year.

Martin Luther understood this: the 95 Theses—points for debate—he nailed to the door of the Wittenberg church in 1517 were inviting Christians to consider whether the racket going on in the church at that time, in which special traveling preachers were taking money to finance the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and promising that in return the devout or their departed loved ones would receive less time in purgatory or, if the donation was really big, a nonstop ticket to heaven.

Neither Martin Luther nor Jesus had any intention of starting new churches. They simply wanted to clear away the clutter that had been allowed to accumulate in the religious practices of their times. clutter that made it hard for people to encounter and be transformed by the presence and grace of God.

And it’s still happening today.

Awhile back Mike was channel-surfing and ran across a particularly obnoxious example of the species televangelist. This guy spent a good 20 or 30 minutes at the beginning of the program asking for money—before he ever mentioned God or Jesus Christ. He read prayer concerns, even cried big crocodile tears over some of them.

The choir came on and sang some song about how we could climb higher and higher. The audience (I hesitate to call it a congregation) clapped and swayed and raised their hands. And as near as I could tell listening from the kitchen, where I was trying to get some supper together for us, the song implied that all the climbing, all the going higher and higher, was up to us—again not once throughout the song was the name of God or of Jesus Christ mentioned.

It was nauseating.

But TV evangelists are too easy a target. If I got up here and did nothing but condemn TV evangelists for, quoting Bono again, “stealing money from the sick and the old,” we could all go home feeling really good about ourselves—sort of like the Pharisee in Jesus’ parable who compared himself to “that tax collector over there” and thought he came out smelling like a rose.[2]

But I’m sorry to have to say this: The goal of coming to church on Sunday is not for everybody to go home affirmed—the congregation or the preacher. And I’m not sure this story lends itself very well to an individualistic interpretation: what are the “money changers” in your own heart, the things you allow to distract you so you can avoid developing an intimate relationship with God?

No, this text is talking to the church as a whole. In this story, Jesus has some very probing question for us.

When we gather here, are we worshiping God? Or are we worshiping the building, our history, our ancestors, our traditions, our way of doing things, or anything else other than God?

In the final analysis, I think the reason Jesus went into the Temple and disrupted business as usual is because in the Temple that day, business as usual had replaced the Lord, the one who delivered us from slavery with a strong hand and a mighty arm, as God. The Temple was no longer a place where God was God, as the Presbyterian pastor in Coffeyville years ago put on the reader board outside his church. That, I believe, is what Jesus objected to.

So the question I think Jesus might have us consider today is this: Is First Christian Church of Butler, Missouri, a church where God is God?

[1] I do NOT mean to suggest, by the way, that since these merchants and money-changers may have been Jewish, this sort of unscrupulous business practice is typical of Jews in that time and this. We’ve all known about plenty of people engaged in shady practices who weren’t Jewish, and being Jewish doesn’t automatically predispose someone to being greedy.

[2] Luke 18:9-14