Sermons

November 16, 2025 (Proper 28)

Not Jehovah

Exodus 34:1-10

I am of the opinion that many of the very best hymns we have available to us come from the Welsh hymn tradition. My favorite is Cwm Rhondda, which is more commonly known as “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah.” We also have a set of words written for that tune by Harry Emerson Fosdick, the founding pastor of the Riverside Church in New York City, called “God of Grace and God of Glory.”

I like both sets, except for one word in the English translation of the original Welsh words. “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah.” (That word, by the way, doesn’t show up in the Welsh version, so it wouldn’t hurt anybody to change it, and some have, to “Guide Me, O Thou Great Redeemer.”)

The reason that word bothers me is that it’s a mistake. I’ll explain, but to do so I need to give you a quick Hebrew lesson.

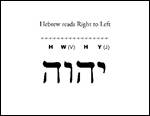

Ancient Hebrew was originally written with no vowels. (That’s the case in modern Hebrew, too; if you’ve seen pictures from Israel you’ll have noticed signs in Hebrew, with just letters, without vowels, which would be shown as dots and dashes above and below the letters.) What’s on screen right now is the Name of God from the Hebrew Bible, just the consonants.

Hebrew is read from right to left, so the consonants of God’s Name are Y (or, in German, J—this will be important in a minute), H, V (or W, in older scholars’ rendering), and H. But there are no vowels there, just consonants. Obviously vowels are needed if a person is to speak a language, but what vowels were used was a matter of tradition or interpretation—you take one word in Hebrew with three letters, or three consonants, and if you say the word with two “a” vowels it’s a verb, but the same word with two “e” vowels or an “e” and something else is a noun.

The third of the Ten Commandments tells us not to make wrongful use of God’s Name. Older translations say, “Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain,” and the word that was rendered as “vain” means “emptiness.” Wrongful use is throwing God’s Name around as though it were just any word, using it to justify misbehavior (“God is on our side” when we are perpetrating violence or injustice, for instance), or making it a swear word.

Many Jewish interpreters through history determined that the best way to avoid misusing God’s Name is not to say it at all. The result of that is that we do not know how God’s Name is pronounced.

Vowels were added to manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible somewhere around 900 ce. But because the Name of God is not pronounced, the scholars who added the vowel points to Hebrew used the ones for a different word, Adonai, which means “Lord,” to help readers remember to substitute Adonai for the Name.

A half-vowel (what in English we would call a schwa), an “o,” and an “a.”[1]

This, incidentally, is what’s behind it any time you find the word Lord in small caps in a Bible passage.

Then a couple hundred years ago, a scholar in Germany was working on translating the Hebrew Bible into German. He evidently didn’t know that the Name had had vowels added for a different word, so he rendered it with the four consonants of God’s Name, but the vowels for Adonai, and ended up with “Jehovah” (because, again, a J in German is pronounced like our Y).

We may not know how God’s Name is meant to be pronounced, but we do know it’s not “Jehovah.”

Well, but you might ask now, why does any of this matter? Who cares if we call God “Jehovah”? Why, to this day, do observant Jews still not use God’s Name—which, again, we don’t know how to pronounce, but our best guess is Yahweh—but substitute “Lord,” or even “HaShem” (which simply means The Name)?

Well, it’s because names are important. I mean, do you like it when someone calls you by the wrong name?

When my nephew Cameron was six or seven, he and I were visiting a friend of mine who had a donut shop. My friend was sitting at the table with me while we were eating our donuts, and another friend of his came by.

Michael introduced Cameron and me to her: “This is my friend Sharla, and this is her trusty sidekick Robin the Wonder Boy.”

After the other friend went on her way, Michael turned to Cam and asked him, “So, if you had a superpower, what would it be?”

And Cam replied, through clenched teeth, “Making you call me by my right name!”

It’s funny, but it’s an important point: our names are very important to us, and we want people to call us what we prefer to be called. Some of us don’t like our given names and go by a nickname, or we use a shortened form of our name, like say “Cathy” for “Catherine.” Others of us prefer not to use nicknames, but want you to call us by the names our parents gave us.[2] Still others have chosen a completely different name for themselves, for one reason or another, and some have even petitioned to have their name legally changed.

But names can have even more meaning.

If you’ve read the Anne of Green Gables books, you might remember that there was a family in those books with the last name Sloane. And at one point someone said about some of them, “They might be perfectly nice, upstanding people; but when all is said and done, they’re Sloanes.”[3] Somewhere along the line, the name Sloane had picked up some dishonor, and nobody with that last name could shed it, no matter how good a person they themselves were.

People talk about having their good name ruined by gossip, or scandal, or false accusations. And it’s hard to get that back. You can go to court and get money damages, but you can’t make people’s minds think differently about you once your name has been scandalized.

We can go even another step further. In some ancient cultures, to know someone’s name meant you had power over them. We can see a vestige of that in the fairy tale Rumpelstiltskin. I think you probably know the story:

A poor miller somehow got audience with the king, and to make himself look better, he bragged to the king that he had a beautiful daughter who could spin straw into gold. Well, the king, like many kings, liked gold and anything that could cause him to have more gold; so he had the daughter brought to the palace and set in a room full of straw. He told her he expected to come back in the morning and find all of that turned to gold.

Of course she had no idea how to do that, and as she sat and wept in her despair, a little man showed up and offered to do it, for a price, of course. This first time she gave him her necklace. A second night she was put in an even bigger room filled with straw, and the little man spun it into gold for the price of her ring.

The third night the king said, “Spin this straw into gold and you shall be my wife.”

The little man came back and said he would do it if, once she became queen, she would give him her firstborn child. Thinking that the king probably wouldn’t actually marry her and make her queen, so she agreed. But he did, and a year later they welcomed their first child.

She had at that point forgotten all about the little man, until he reappeared and demanded that she give him what she had promised. She was horrified, but he insisted. He did, however, give her an out: “I will give you three days, and if by that time you find out my name, you may keep your baby.”

So she thought up all the names she had ever heard, and on the first day she told them to him, but none of them was his name. She sent messengers out to find out what people were called, but none of those names was the right one, either.

On the third day a messenger who hadn’t made it back the day before showed up. He said, “I wasn’t able to find out any new names; but I came to a high mountain at the end of the forest, and there was a little house. In front of the house there was a fire burning, and around the fire a ridiculous little man was jumping up and down shouting:

‘Today I bake, tomorrow brew,

the next I’ll have the young queen’s child.

How glad am I that no one knew

that Rumpelstiltskin I am styled.’”

When the little man showed up that day, she said, “I wonder if your name might be Rumpelstiltskin?”

And he was furious. “The Devil has told you that!”

In his anger he stamped his right foot so hard that his whole leg went into the earth. Then, trying to free himself, he stamped his left foot until it sank into the ground too; and the earth swallowed him up and closed itself behind him, and the little man was never seen again from that day to this.[4]

It was because the queen knew the man’s name that she was able to banish him and get out of the ill-conceived bargain she had made with him.

In the ancient world, if you knew someone’s name you could have some power over them. And, as we see in today’s reading from Exodus 34, a name brings with it meaning—it’s why a lot of the time in the Bible a person’s name is changed when they encounter God, like Jacob becoming Israel, “one who struggles with God”;[5] or Simon becoming Peter, “the rock,” upon which Jesus promised to build his church.[6] I think that’s one reason why we’re commanded not to misuse God’s Name, and I think it’s one reason many people, not just Jews but many Christians including myself, do not say the Name.

Every time we pray the Lord’s Prayer, we are reminding ourselves why we must handle God’s Name with care. God’s Name is hallowed—hallowed is an old English way of saying holy. Holy means “set apart,” or “other.” It’s not something ordinary, a word we throw around in casual conversation with no meaning at all. Nor is it something we use to justify our actions.

In the very first episode of the BBC series Father Brown, featuring Mark Williams (also known as Arthur Weasley for those of us who’ve seen the Harry Potter movies), we are shown a rare flash of anger from the crime-fighting priest. A colleague of his has just confessed to murdering his own brother, who was a real scumbag, proclaiming that he has done the Lord’s work. And Father Brown almost slashes his face open with his words: “God is not your scapegoat.”

We, like many Christians, say the Lord’s Prayer together in worship every Sunday, and many of us also include it in our daily prayers.

There is a tension in the first two phrases of the Lord’s Prayer. First we’re taught to call upon God as a loving Father. But we immediately remind ourselves that our loving Father is holy—God is Other, apart from us; God’s ways are not our ways, and God’s thoughts are not our thoughts[7]—so much so that even God’s Name carries with it great power that must be handled carefully.

In Proverbs it says—and this found its way into a worship song that was popular when I was in seminary—“The Name of the Lord is a strong tower; the righteous run into it and are safe.”[8] And in the old prayer known as St. Patrick’s Breastplate, the one praying binds the Name of God around themselves as one would put on a suit of armor.[9]

So as we begin to say the Lord’s Prayer, we shift the focus from ourselves, from what we think is important, to the One we call our Father. And we are reminded of something very important about that One: God is holy, set apart from us, powerful, not just a kindly old man like Santa Claus, who with a twinkle in his eye gives us everything we ask for. This One is not like us. We cannot fully understand God, nor how God does business, and we do well to remember that even God’s Name has more power than the most powerful weapon humanity has ever devised.

God is good, as C.S. Lewis said, but not safe.[10] In Christ we have been made welcome to run to God as children would run to a loving Father; but God is much, much more than that.

O Adonai and Lord of the house of Israel,

you appeared to Moses in the flame of a burning bush,

and at Sinai you gave him the Law:

Come with your outstretched arm to save us.

[1] I used a small “a” for the schwa and a capital “A” for the regular “a” because my computer keyboard would not, no matter how hard I tried, give me the upside-down “e” that is supposed to indicate a schwa.

[2] I’m one of these, by the way; some of my relatives call me “Shar,” but I would rather not have anyone outside my family call me that.

[3] I think this might have been in Anne of the Island.

[4] This was one of the fairy tales collected by the Brothers Grimm. It’s folklore, so it exists in multiple versions; a slightly different one can be found at https://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/rumpelstiltskin.

[5] Genesis 32:28

[6] Matthew 16:18; Peter is Greek; the Aramaic equivalent is Cephas, the name Paul generally uses when he talks about Peter.

[7] Isaiah 55:8

[8] Proverbs 18:10

[9] See https://www.catholictradition.org/Litanies/litany41.htm for a version of the full text of this prayer.

[10] This is from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, an allegorical retelling of the Gospel.