Sermons

October 12, 2025 (Proper 23)

“You’re hearing things.”

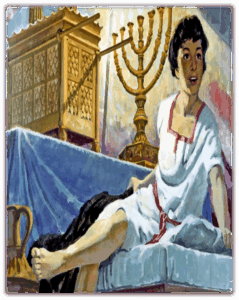

1 Samuel 3:1-21

When my sister and I were teenagers, we had friends who would sometimes come to our windows at night. It happened to her more than it did to me. A couple of Carrie’s friends worked at Wendy’s, where some of the food that was prepared and not sold had to be thrown out at closing time. They would sometimes bring some of the leftovers to her at 11:00 or midnight. Now and then she’d get a Frosty, if they were cleaning out the machine that night.

The most memorable time friends of mine came to my window in the middle of the night was the night after I came home from Ireland. There is a six-hour time difference between Ireland and Kansas, so my body thought it was 8 a.m. when it was actually 2, and I was wide awake with the lights on. And a couple of my friends came to my window and knocked, then called out my name.

I didn’t answer them. Figured if they really needed something they could go to the front door and ring the bell like civilized people—except that civilized people don’t, barring emergency, come around at 2 a.m.; and if they did, they were likely to be greeted by my dad, who wouldn’t have been especially friendly to them.

Strange voices calling your name in the middle of the night are unnerving.

I wonder if Samuel was creeped out by the voice that called his name. It was probably closer to daybreak than when Carrie’s and my friends would knock on our windows and call our names. We know this because of one detail the text gives us: “the lamp of God had not yet gone out.” The lamp of God, a visible symbol of God’s presence in the sanctuary, burned all night, but would have run out of fuel around dawn. Since the lamp was still it, but apparently could be expected to go out soon, it’s likely that Samuel heard the voice calling his name during that darkest hour that comes right before dawn, when every sound is magnified and every problem seems bigger and more frightening than it does by light of day.

Samuel didn’t recognize the voice, but since he and Eli, the old priest who was training him, were the only ones there, he could only assume it was Eli. Maybe Samuel thought his voice was different because there was something wrong. But when he went into Eli’s room, he found out Eli wasn’t the one who had called him.

This happened three times, Samuel running to answer the call, thinking each time that it was Eli. Finally, the third time, it dawned on Eli who the voice really belonged to.[1] So he tells Samuel the correct way to respond if the voice called out to him again: “Speak, Lord, for your servant is listening.”

Samuel goes back to his bed, and when he hears the voice calling again, he answers as Eli had instructed him.

The Sunday school version of the story ends right there, and there are certain lessons for children to learn from that version: God speaks even to children; God gives us important jobs to do, even if we’re very young or very old; and when we hear God calling us, we need to answer.

But the Sunday school version is incomplete, and the meaning we draw out of the story when we hear the whole thing may be different.

Of course the moral of the story as we learned it in Sunday school is true; God does speak to children, God does give people important work to do, and we should indeed answer God’s call. But we miss something when we stop before we find out what God had to say to Samuel.

The Sunday school version also tends to leave something out of the very first verse. We heard that the boy Samuel was ministering to the Lord under Eli, yes. But I don’t remember anybody ever saying much about the second half of the verse, which says, “The word of the Lord was rare in those days; visions were not widespread.” That’s the language of prophecy; in the prophetic books, oftentimes a prophet’s message begins with “The word of the Lord came to me…”[2]

Maybe that’s why Samuel didn’t recognize God’s voice that night. Maybe he hadn’t heard the word of the Lord from a prophet or anyone else up to that moment.

But why was the word of the Lord rare? Why weren’t people seeing visions? Maybe it’s because nobody expected to hear God speak or receive visions from God. Maybe God was like my friends knocking on the window when I refused to answer them. Maybe people were busy doing their own things, only going through the motions of religious observance, but otherwise conducting themselves as if there were no such thing as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who had brought them out of enslavement and given them the Promised Land to settle. I’ve heard it called “practical atheism.” They gave lip service to a belief in God, but their lives reflected that God didn’t mean a whole lot to them.

Or maybe—and this is where the first verse connects to the part of the chapter after the Sunday school lesson ends—people weren’t hearing the word of the Lord because the people who were supposed to be serving the Lord had become corrupt, only out for themselves.[3]

Eli was elderly and losing his sight. His sons were serving as priests—priesthood was generally hereditary—but they were no good.

If we go back into chapter 2 of 1 Samuel, after Hannah’s song of praise to God when she takes Samuel to Shiloh to begin his training, we find out exactly what it was they did. When people brought their offerings, these two priests, Eli’s sons Hophni and Phinehas, would take the best for themselves. Sometimes they would even threaten to take it by force if their demands were not met.

People were bringing their offerings to God as they had been taught to do; perhaps in some cases these offerings represented real sacrifice, if not hardship. But Hophni and Phinehas treated those sacrifices with contempt, by taking the best and biggest portions for themselves and thus living extravagantly on the backs of potentially poor others.[4]

And the way the two young priests mistreated the women who served as greeters at the entrance to the sanctuary might have escaped the notice of the worshipers, but God saw.

Eli, who knew what was supposed to be done, either didn’t know what they were doing, or knew but didn’t even try to put a stop to it.

There is often a disagreement between Christians who are more socially liberal and those who are more conservative about the nature of sin. On the one side are folks who see sin as an individual problem, someone behaving badly and contrary to what God expects of us. On the other side are folks who see sin as systemic, in which the gravest sins are the ways in which societies, communities, and governments mistreat and oppress people.

I think they’re both right, and this story is a perfect example.

Eli’s sons behaved badly. Eli looked the other way. These were individual sins, individual people disobeying God. But their bad behavior had consequences for others, and even created a system that was sinful. Poor people were being robbed, essentially, to fund an extravagant lifestyle for Hophni and Phinehas. The sacrificial system, which had been set up both to allow the people access to God and, yes, to provide for the priests, who had no other means of support, had become a way for two young men to enrich themselves.

God wasn’t especially relevant to them, either; they had been born into a system that was supposed to be about worshiping and serving God, but they had turned it into a cash cow—dare I say a den of thieves. Individual sin led to systemic sin; and before too long the whole thing was rotten to the core.

So when God called to Samuel in the wee hours of the morning, the darkest hour that comes just before dawn, the message he wanted to deliver was a heavy burden on the shoulders of a little boy.

The message was that God had had enough.

We can gloss it over and say that God’s message to Samuel was about the end of one era and the dawning of another. But that ending and beginning are happening for a reason, and the reason is that the people who were supposed to be leading Israel—remember this was before they had a king—had become corrupt. The sin at the heart of that corruption was greed, and greed is a form of idolatry: wealth, power, and possessions occupying the position that ought to belong to God alone.

Samuel lay on his bed until the sun came up, the message with which God had entrusted him rolling over and over in his head. The message was that the greed of Eli’s sons had gone so far that there was no turning back; there was no sacrifice or prayer that would be enough to get them back on God’s good side.

Samuel had to have worried about how Eli would react to it. Would he be angry with God? Would he be angry with Samuel—or take out his anger at God on Samuel, turning him out of God’s house or even harming him in some way?

Samuel awaited the dawn, the moment when he would have to go talk to Eli, with fear and trembling.

And Eli did threaten Samuel—but not like he had feared. Eli must have had at least an inkling what was up, because the threat was essentially that whatever Samuel was there to announce should happen to Samuel himself if he didn’t tell Eli everything he had heard from God.

Eli’s response to the message is interesting. “It is the Lord; let him do what seems good to him.” (In other words, “Thy will be done.”)

He knew that God’s judgment on him and his sons was righteous. He knew the system Hophni and Phinehas were exploiting was sick, because of their behavior which their father had ignored, and was going to have to be overhauled. He knew that their greed would have to be cut out of the temple and sacrificial system like cancer needs to be cut out of the body, because that greed was killing not just the religious institution, but the people of Israel.

It was the darkest hour before the dawn when Samuel heard God’s voice; but now the sun was coming up on a new day.

[1] We lose in translation from Hebrew to English a little play on words. The two main characters in today’s story, other than God, have names whose meanings are a bit ironic given what’s happening in the narrative. Samuel—in Hebrew Shmuel—means “God has heard.” But it’s Samuel and Eli, not God, who need to listen up in this story. And Eli means “my God”—we see that in Jesus’ quote of Psalm 22, verse 1, from the cross: Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Eli is obviously not God, but as a priest, he represents God, and to Samuel, serving Eli at Shiloh was essentially the same as serving God.

[2] See, for instance, the call of Jeremiah in chapter 1 of his book, and the subsequent message in the second chapter.

[3] This is something that has been true of some religious leaders in every time and place, including the days of Jesus, the Middle Ages, and our own time.

[4] Bono once accused the TV evangelists of the 1980s of “stealing money from the sick and the old.”